Implanted Telescope Restores Sight To Blind

Remarkable optical system that treats central vision blindness caused by end-stage macular degeneration recently received FDA approval.

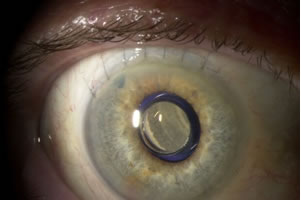

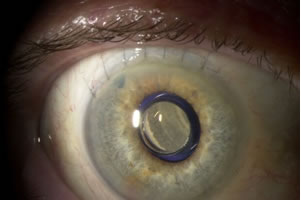

Implant in situ

The challenges involved in developing an implantable optical device to give sight back to sufferers of end-stage age-related macular degeneration (AMD) are nothing short of immense. Not only must developers understand the disease and create a device that will bring maximum benefit to the patient, there are biocompatibility and sterility issues to address – plus of course the key issue of how to implant the device into the eye itself.

But following a clinical trial involving more than 200 patients at 28 leading ophthalmology clinics across the US and now with the all important FDA approval under its belt, VisionCare Ophthalmic Technologies, a privately held specialty medical device company based in California, is finally in a position to offer end-stage AMD patients its implantable telescope technology.

“Our device is the first of its kind. It is the first FDA-approved implantable medical device demonstrated to improve visual acuity and quality of life in individuals with end-stage AMD,” Chet Kumar, VisionCare’s VP of business and market development, told optics.org. “There is truly an un-met need for these patients as no drugs or surgical procedures are available to reverse the effects of macular degeneration.”

What is end-stage AMD?

A healthy eye uses several elements, such as the lens at its front, and the light-sensitive retina at its rear, to provide clear vision. Packed with a high density of light-sensitive cells, the macula is a small area of the retina that produces the highest-resolution images used for central vision. AMD is a disease of the macula that leads to varying levels of central vision loss.

In the case of end-stage AMD, a patient will suffer from complete central vision blindness, which is permanent as currently there is no way to repair the macula. Estimates suggest that as many as 750,000 people in the US are currently suffering from end-stage AMD, living with a central blind spot in both eyes.

Fortunately, the cells that are responsible for peripheral vision – albeit at a lower resolution than central vision – are not attacked by AMD. And this is what VisionCare exploits with its implantable telescope technology. “In the simplest terms, our device helps patients to see by projecting the central image around the degenerated macula instead of on to it, thus utilizing healthier, preferred retinal photoreceptors,” explained Eli Aharoni, the VP of research and development and general manager of VisionCare Ltd.

Getting started

VisionCare was founded in Israel in 1997 to commercialize the implantable telescope technology that was the brainchild of an ophthalmologist called Isaac Lipshitz and prolific inventor Yossi Gross. In 2000, the company restructured and moved its headquarters to the US, where it is now led by president and CEO Allen Hill. Its research and manufacturing activities remain in Israel and are headed up by Eli Aharoni. To date, the company has raised a total of $59 million in venture capital funding.

As Aharoni explains, simply knowing where to start was a major difficulty. “The initial challenges were in understanding the disease and then how to build a device that can meet the patient’s needs,” he said. “We had to consider many optical parameters, the mechanical engineering to produce the device to tight tolerances, the biocompatibility of our materials and their sterility and stability inside the eye. The final task was to develop a surgical procedure to implant it in the eye, which was a challenge requiring coordination between both engineers and surgeons.”

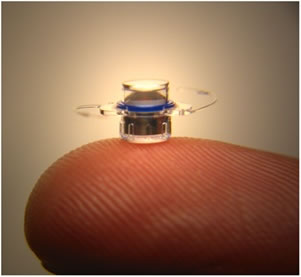

Implantable device

The optics involved

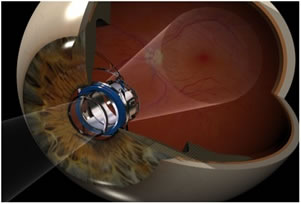

VisionCare’s implantable telescope projects an image that would normally be destined for the damaged macula onto healthy retinal cells instead. However, as cells in this peripheral retinal location generate images at a lower resolution, it is essential to magnify the image.

“Unfortunately, if you take any image and magnify it, the field of view decreases,” commented Aharoni. “When we magnify the image on to the retina, instead of having the naturally wide field of view of a normal eye, people have a limited and smaller field of view. A normal eye has a detection field of view of anywhere between 90 to 130 degrees, not necessarily all at high resolution. Our two telescope platforms are wide-angle, offering a magnification of 2.2x and 3x with a relatively large field of view of 24 degrees and 20 degrees, respectively.”

To enable patients to compensate for the peripheral retina being used for central vision, VisionCare only implants its telescope technology into one eye. The implanted eye restores the patient’s central vision, while the untreated eye retains peripheral vision for mobility and orientation. Although this sounds disconcerting, patients are reported to adapt within a few weeks.

The telescope is implanted in an outpatient procedure and involves removing the eye’s natural lens. “The patient’s natural lens focuses images onto the macula, but in end-stage AMD, the macula is no longer functioning and providing central vision,” explained Kumar. “The telescope implant is surgically placed in the capsular bag after the lens has been removed. We essentially use the space where that natural lens was to secure the telescope implant.”

Measuring just 3.6 mm in diameter, the implantable telescope is essentially a telephoto device that, in combination with the cornea, creates a telescopic effect that magnifies objects in view. The device is composed of a sealed glass capsule which contains all of the bi-convex and bi-concave convergent and divergent micro-lenses confined within air pockets to create a magnified image on the retina.

“Our manufacturing process is unique to our company,” commented Aharoni. “Everything is done in a Class 10 clean room. We have developed special machines and processes that allow us to produce the devices with micron-level precision.”

Image magnification

Clinical trials

VisionCare has now completed two clinical trials. An initial trial ran from 2000 to 2002, while the pivotal clinical trial started in 2003 and led to the recent FDA approval. This trial involved many high profile and leading ophthalmology institutions, including the Johns Hopkins University, the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and the Wills Eye Institute in Philadelphia.

“The pivotal trial showed that we can improve visual acuity on the eye chart; improve a patient’s quality of life because of the vision we can give back, and finally that the telescope can be implanted safely,” commented Kumar. “We have long-term data with patients five years down the line post-surgery. That’s why the FDA ophthalmic devices advisory panel unanimously recommended our technology for approval.”

Ophthalmologists involved in the study also sing the praises of the implantable telescope technology. “Despite the past decade of advancements in macular degeneration therapies, retina specialists still did not have a treatment for the many wet- and dry-AMD patients who progressed to end-stage disease,” said Julia Haller, Ophthalmologist-in-Chief of the Wills Eye Institute. “Starting today, we can provide these patients with new hope.”

“This is truly a breakthrough technology for AMD patients as their treatment options have been limited until now,” added Kathryn Colby, an ophthalmic surgeon at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. “The clinical results from the pivotal FDA trial have proved that we can place this tiny telescope prosthesis inside the eye to help patients see better and, for some, even to levels at which they can recognize people and facial expressions that they could not before.”

According to Kumar, many ophthalmic institutes are now interested in becoming treatment centers. Here, the patient would undergo a strict screening process to ensure that they would benefit from the devices before having surgery. Centers would also provide post-operative care and training on how to adapt to the new levels of vision. “We initially plan to launch across the US, and then expand to Europe and beyond,” commented Kumar.

Profile view - schematic

What the patients say

So, what has been the reaction of the patients who have received the sight-restoring treatment? Kumar says that they often recount how difficult life was before they had the surgery, especially in social and dynamic activities, and how much of a difference the implant has made. “For example, some patients have said, before I had this, I wasn’t able to see your face,” he commented. “In terms of the implant only being in one eye, some patients have explained that you just adapt over time and eventually don’t think about it. With these patients, neither eye has a functioning macula, so there is no permanent way around the blind spot. Even though the image in one eye is bigger than the other, they have commented that it just becomes natural – a goal of Eli’s and [testament to] his engineering team’s efforts.”

About the Author

Jacqueline Hewett is a freelance science and technology journalist based in Bristol, UK.